Since we announced the 39 recipients of our Beanstack Black Voices Microgrants in December, librarians, educators, and administrators across the country have used their funds to create real change in their communities. From J.T. Moore Middle School’s virtual visit with author Nic Stone to Galesville Public Library’s commitment to providing their patrons with more diverse books, each new initiative reinvigorates our commitment to racial justice.

Today, we’re shining a light on the hard work of librarians and administrators in four microgrant-winning Maryland libraries and library systems. During the isolation of the pandemic and the growing equity gap of remote learning, they found creative ways to reach under-served communities and spark enlightening conversations.

“It’s not just about logging minutes or books—which is all important,” said Carrie Sanders, Youth Services Coordinator at Maryland State Library. “It’s evident that through this kind of an opportunity, it’s more [about] how to really actualize and maximize our kids and give them the best foundation and life skills and experience to set them up for success. It’s what we all want. We want them to grow up happy and healthy and whole.”

Sanders hosted a virtual roundtable in March where each of the Maryland microgrant winners discussed their projects and its impacts. One big takeaway was just how big a difference a microgrant can make. “Look what happened out of just a little bit,” she said. “This might be a spark for something else that you can do that doesn’t necessarily require lots of funds.”

Cheryl Sidwell and Barb Graham at Wicomico Public Libraries

When the pandemic hit and Wicomico Public Libraries’ branches closed, Events & Development Manager Cheryl Sidwell noticed an immediate need to transform how they delivered essential library services to their most vulnerable populations.

The staff sprung into action with a hotspot lending program and more community outreach than ever before. Through Sidwell’s work with the Lower Shore Vulnerable Populations Task Force, she connected with key leaders in the growing Haitian and Hispanic communities and honed in on a need for more bilingual materials in Spanish and Creole.

“Suddenly, learning’s taking place at home and you don’t have people able to help you with your homework,” Sidwell said. “So when I saw this grant, I really wanted to get more bilingual books.”

With money in hand, Wicomico County’s Youth Services Manager Barb Graham took on the task of tracking down titles in Spanish and Creole. Then the staff started giving away the diverse books at pop-up One-Stop-Shop events, where the county’s vulnerable population task force assembles free community resources, supplies, and information.

“Some of the parents take these books and use them as presents for their children,” Graham described. “We’re just trying to get books into people’s hands. We have so many new folks in our community who are learning English … The more we can do, the more we can help.”

Michelle Hamiel at Prince George’s County Memorial Library System

As one of the first libraries to join the Beanstack family, Prince George’s County Memorial Library System has always been a trailblazer. Chief Operating Officer for Public Services Michelle Hamiel specializes in creating connections throughout the community, whether that be at the county detention center or at local subsidized housing complexes. And like Sidwell in Wicomico County, she quickly saw disparities grow when schools closed in 2020.

The library system sent older computers and laptops to apartment complexes’ community rooms. It also installed WiFi to help kids access classes and help parents connect to community resources. But the community rooms lacked one important thing.

“Not only were these kids probably suffering from online school, but they didn’t have access to books,” Hamiel said. “It’s important that children have access to books and materials with characters that look like them.”

With microgrant funds, Hamiel purchased diverse book baskets with titles in Spanish and English to put out in community rooms. The idea, she said, is that when kids come down to use the computer themselves or with a caregiver who needs to get online, they can bring a book home with them or read it there while they wait.

“We want to get books in the hands of the children. If they [the books] come back, great. If they don’t, we have enhanced their library in their home,” Hamiel said. She described one property manager who was “delighted,” when she realized the books would be free for the kids’ taking.

“We are taking the library to the children, because many of those children don’t come to the library, especially if the library is not within walking distance,” Hamiel said. “We want to make sure they know the library is for them as well.”

Angelica Candelaria at Caroline County Public Library

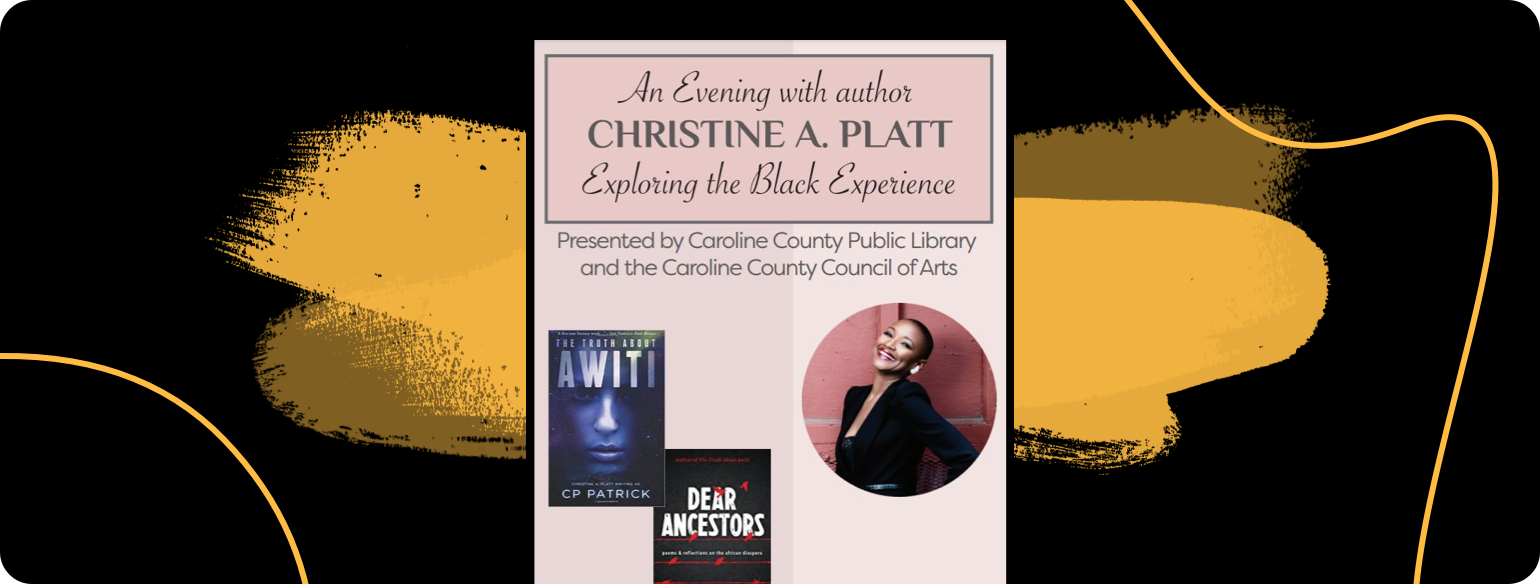

Representing diverse viewpoints and increasing community understanding were the twin motivations behind Caroline County Public Library’s microgrant initiative. With half of their funds, they partnered with the Caroline County Council of Arts to host their first-ever virtual author event and brought in Maryland author Christine A. Platt.

“We wanted to bring her to the library so that they could learn from her vast knowledge, to bring African American culture to the forefront, and also to use her reading to spark discussion and understanding,” said Youth Services Manager Angelica Candelaria.

With the author talk fully virtual, the library sent out hotspots to interested patrons and hosted an online discussion to give community members a platform to engage and learn from each other and the author.

The other half of their microgrant went to purchasing diverse books for the library, including many of Platt’s own books. Candelaria thoughtfully researched and selected youth literature that focused on Black voices and experiences. Some of the titles she added to their collection were Stamped (For Kids): Racism, Antiracism, and You by Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi, The Only Black Girls in Town by Brandy Colbert, and Me & Mama by Cozbi A. Cabrera.

“When I set out to purchase these books, I wanted to represent African American lives in different aspects,” Candelaria said. “I didn’t want to just buy one voice. Being a Hispanic person, I know that sometimes books are bought just about one viewpoint of a person of color, so I really wanted to get a vast kind of plethora of books showing different viewpoints of the African American experience.”

Kathy Breihut at Worcester County Public Library

For Worcester County Public Library, the Beanstack Black Voices microgrant aligned with other funding to maximize their yearlong Read Woke challenge and specifically grow teen engagement.

Youth Services Manager Kathy Breihut originally planned to use their funding to purchase diverse books in each of the challenge’s categories, but another substantial grant ended up covering the book purchases. With the windfall, Breihut decided to target their most reticent patron population: teenagers.

“Historically, we’ve had a hard time getting teens to sign up for anything,” Breihut said. “So we decided to use the money for two $500 prizes. And we’ve been advertising all over the place.”

The library is hosting monthly discussions just for teens, with each program centered on one type of diverse voice. Teens read a book from the corresponding Read Woke booklist that Breihut developed, write a short review, and then attend a Zoom meetup to discuss what they learned with their peers in order to be eligible for the prizes.

With substantial outreach on social media and across other library programming, attendance has grown every month. Some teens are even going above and beyond the requirements. “Participants are not just reading one book,” Breihut reported. “They’re reading two or three from the list, which was not something that we’d anticipated.”

And with the exposure to new ideas, voices, and viewpoints, she hopes the diverse reading lists and discussions will have a ripple effect throughout their community. “I like the idea that we are educating the teens, and then hopefully they’ll have conversations with the adults in their families,” Breihut said. “I’m thankful to be a part of it.”

Learn More

See how the Beanstack Black Voices initiative began.